Nike CEO Steps Down: Revisiting John Donahoe’s Legacy through Nike’s Acquisition of RTFKT

Source: RTFKT

On September 19th, 2024, Nike’s CEO, John Donahoe, announced he would be stepping down from his position, leaving behind a tenure marked by significant transformations in Nike’s business model. Taking the reins in early 2020, Donahoe guided the company through a global pandemic, supply chain disruptions, and shifting consumer habits. But above all, his leadership was defined by Nike’s push into e-commerce and direct-to-consumer (DTC) strategies—an approach that saw Nike lean heavily into digital channels and focus on selling directly to customers rather than relying solely on third-party retailers.

One of Donahoe’s most notable moves was Nike’s 2021 acquisition of RTFKT, a company specializing in digital collectibles and NFT-backed sneakers. This deal was a bold step into the metaverse, positioning Nike as a pioneer in digital fashion and aligning with Donahoe’s vision of an increasingly digital retail landscape. Yet, despite these forward-thinking moves, Nike has faced challenges under Donahoe’s leadership, including a downturn in stock prices and concerns about market saturation. As he steps down, the question remains: What does the future hold for Nike—and for retail at large?

Source: CNBC

The RTFKT Acquisition: A Deal Analysis

On November 13th, 2021, Nike announced the acquisition of RTFKT, a creator-led organization producing digital artifacts, in particular sneakers, backed by NFTs. The deal would allow Nike to exploit the possibilities of the metaverse, leveraging RTFKT’s expertise and community. As announced by the CEO, this transaction serves Nike’s digital transformation objective, and it is the 6th acquisition since 2018 focusing on the digital side of retail.

Company Overviews:

Nike

Nike, Inc. is an American athletic footwear and apparel corporation headquartered near Beaverton, Oregon, United States. It is the world's largest supplier of athletic shoes and apparel…

Let’s be honest, unless you’ve been living under a rock since 1964, we all know what Nike is and what it is that they do. But given that Shoe Dog might just be my favorite memoir ever, we might as well spend some time and start from its beginning.

Even though Nike and its iconic swoosh that we know today was officially founded in 1971, the story of Nike is inseparable from Phil Knight's journey - from selling Japanese shoes from his car trunk to building one of the world's most valuable brands. His combination of introversion and relentless drive, his willingness to bet everything repeatedly, and his vision of what athletic footwear could become shaped not just a company, but how the world thinks about sports, marketing, and the relationship between athletes and consumers.

Phil Knight, by his own description, was an unremarkable track athlete at the University of Oregon in the late 1950s, running a 4:13 mile that he modestly called "decent." (Personally, having been a cross country and distance track athlete in high school, there is no way someone with a 4:13 mile can be called an “unremarkable” athlete. That is crazy fast, especially before all these technological advancements in running shoes led by who other than Nike and Bill Bowerman himself) But actually, his mediocrity as a runner would prove fortunate - it made him the perfect test subject for his coach and future business partner, Bill Bowerman's endless shoe experiments, a relationship that would change both their lives and the future of athletics.

At Stanford Business School, Knight became obsessed with an idea that seemed obvious to him but crazy to everyone else: Japanese shoe companies could do to German athletic shoe manufacturers what they'd done to German camera makers - offer comparable quality at lower prices. His professor gave the paper a decent grade but wasn't particularly impressed. No one was. The athletic shoe market seemed tiny, a niche within a niche.

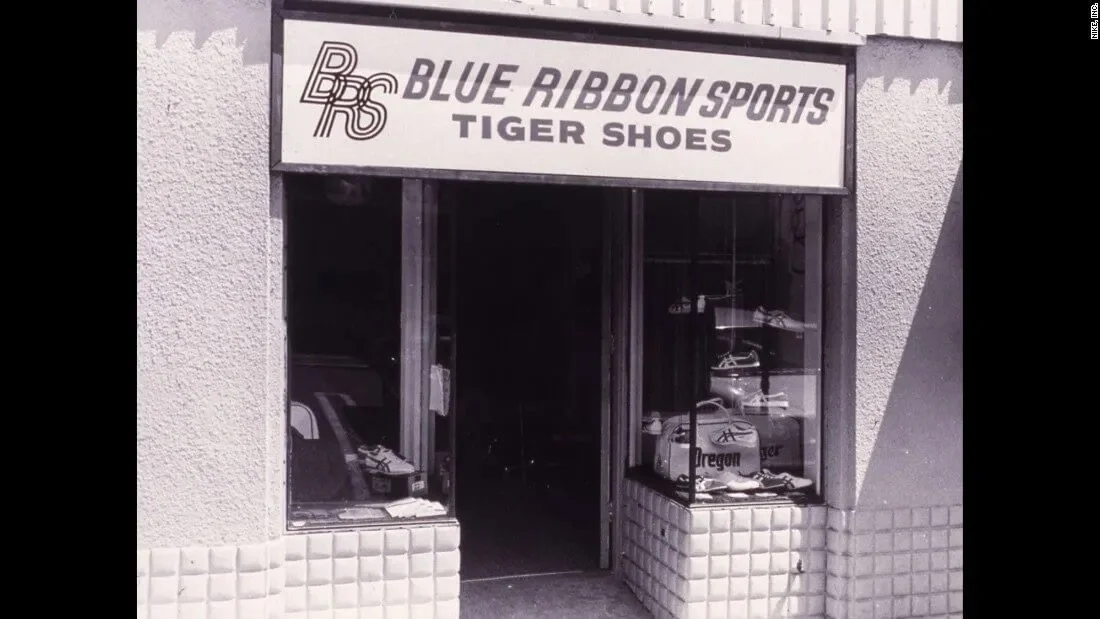

But Knight couldn't shake the idea. After graduation in 1962, he set off to travel the world, which was really a pretense to a strategic visit to Japan. In a moment of uncharacteristic boldness for an introvert, he bluffed his way into Onitsuka Tiger's headquarters in Kobe, presenting himself as an American distributor. The company didn't exist yet - he made up the name "Blue Ribbon Sports" on the spot, possibly inspired by a beer billboard he'd seen the night before and the ribbons he used to win in track races as a kid. When asked about market research, he confidently cited numbers he'd fabricated entirely. Somehow, it worked. The birth of Blue Ribbon Sports then began with a $50 wire transfer to Onitsuka Tiger in 1963, where Knight had to ask his father to send the money while he was still in Japan, hoping to receive sample shoes at his family's Portland address. Yet, when Knight returned home months later and eagerly asked his parents about the shoes, they had no idea what he was talking about. The samples wouldn't arrive for nearly a year - an early lesson in the challenges of international business.

Source: The Olympians

During this waiting period, Knight took a job as an accountant at Price Waterhouse and became a CPA. When the Tiger shoes finally arrived around Christmas 1963, Knight immediately took a pair to Bowerman at the University of Oregon. Here's where Knight's business instincts first showed - he wasn't just trying to sell shoes to Bowerman, he was hoping to get the influential coach to have his runners wear Tigers. To his shock, Bowerman countered with a much bigger proposal: "Let me be your partner."

The partnership agreement they struck was telling: Bowerman would get 49% and Knight 51%. Bowerman insisted Knight keep majority control because, as he put it, "I don't know anything about business." Each man invested $500, and Blue Ribbon Sports was officially founded on January 25, 1964. The entire initial order was for 300 pairs of Tigers, costing $1,000. Knight sold the first shoes out of his green Plymouth Valiant at track meets across the Pacific Northwest. Despite being naturally introverted and previously failing at sales jobs, Knight found he could sell shoes easily - the first indication that passion could overcome his shyness. That first year, they sold $8,000 worth of shoes. The number seems tiny now, but it was enough to order more.

1965 brought their first full-time employee, Jeff Johnson, a former competitor Knight had met at Stanford. Johnson was, in many ways, Knight's opposite - outgoing, talkative, and absolutely fanatical about running. He would write letters to customers asking about their shoe preferences and injuries, creating the first customer database. He also opened Blue Ribbon's first retail store in Santa Monica, California, operating it out of a tiny space while living in a nearby apartment so cramped he had to sleep on top of shoe boxes.

The business model in these early years was incredibly precarious. Their profit margin was razor-thin: they sold the shoes for $6.95 while paying about $3.50 per pair. After factoring in Johnson's commission of $1.75 per pair, they were left with less than $2 profit on each sale. This created a constant cash flow problem - they needed money to order inventory but could only get small loans from banks based on their existing assets. But Bowerman's contribution during this period was invaluable. He was constantly experimenting with ways to improve the shoes, using his runners as test subjects. He would take Tigers apart, modify them, and send detailed suggestions to Onitsuka. His most significant early innovation was the Tiger Cortez, featuring a full-length midsole, an innovation that would become standard in running shoes.

Source: Amazon

By 1966, sales reached $44,000, doubling to $84,000 in 1967. Each growth spurt required more capital for inventory, forcing Knight to maintain his teaching job at Portland State University. This is where he met two crucial people: Carolyn Davidson, the student who would design the Swoosh and Penny Parks, his accounting student who would become his wife.

The late 1960s saw Blue Ribbon expanding beyond just track shoes. Bowerman wrote a book called "Jogging" in 1967, helping spark a recreational running boom in America. Before then, running seemed like something only a madman would engage in. Who would go out and just jog for fun? I guess that’s how I felt too, before I fell in love with cross country. Nonetheless, the book's success proved prescient - running was about to transform from a niche, nerdy hobby into a mass phenomenon. Throughout these years, Knight maintained a "grow or die" philosophy, regularly operating at a 100% debt-to-assets ratio. Every dollar that came in went straight back into inventory. The company was perpetually on the edge of bankruptcy, saved only by its continuing growth and Knight's skillful financial juggling. When they asked for more financing from Oregon banks in 1970 to support their growth, the banks balked - leading Knight to discover the existence of Japanese trading companies like Nissho Iwai, which would eventually help finance Nike's creation.

By 1969, sales hit $300,000, and by 1970, they passed $1 million. But success brought new challenges. Onitsuka Tiger was growing uncomfortable with Blue Ribbon's size and success. They started asking questions about Blue Ribbon's business practices and making noises about taking over U.S. distribution themselves. The fundamental problem was that Blue Ribbon's success had made them too big to be just a distributor but too dependent on Tiger to be truly independent.

1971 marks the end of Nike’s earliest chapters, with Blue Ribbon doing about $2 million in annual sales, owning nearly 70% of America's running shoe market. But the entire operation was dangled by a thread, as Nike was still completely dependent on Onitsuka Tiger for their product supply. The first signs of trouble emerged when Knight discovered that Onitsuka representatives had been secretly meeting with other potential American distributors. In a moment of either brilliance or recklessness, Knight engaged in some amateur “espionage.” During a visit from Onitsuka executives to Blue Ribbon's headquarters, one of them left his briefcase behind during a bathroom break. Knight seized the moment, quickly photocopied its contents, and discovered documents confirming his worst fears: Onitsuka was indeed planning to cut them out and take over U.S. distribution themselves.

Rather than confront Onitsuka immediately, Knight played a dangerous double game. When Onitsuka offered to buy 51% of Blue Ribbon Sports at book value (essentially nothing, given their debt-heavy structure), Knight stalled for time, responding with polite but noncommittal letters. Meanwhile, he was secretly laying the groundwork for Nike's creation.

The situation grew even more complex when Knight discovered the existence of Japanese trading companies - particularly Nissho Iwai, which could provide both financing and manufacturing connections. When Knight mentioned to Onitsuka that he was considering working with Nissho Iwai for financing, they immediately objected. Their reaction confirmed Knight's suspicions: Onitsuka knew that trading companies like Nissho Iwai could help Blue Ribbon establish direct manufacturing relationships in Japan, effectively cutting Onitsuka out.

In a bold move that showed just how far Knight had come from his introverted accounting days, he decided to fire the first shot. While still selling Tiger shoes, he secretly contracted with a factory in Mexico to produce his first Nike shoes - football cleats that wouldn't technically violate his Tiger contract since Onitsuka didn't make football shoes. This is where the famous Swoosh was born, along with the Nike name, though neither was intended to become what they are today - they were originally just meant for this side project.

The situation reached its breaking point in 1972 when Onitsuka discovered Nike's existence. Legal battles ensued, with Onitsuka claiming breach of contract and Blue Ribbon arguing that Onitsuka had violated their agreement first by planning to end the relationship. The courtroom drama included the embarrassing revelation of Knight's spy tactics when his memo about hiring a Japanese spy surfaced during discovery. In a twist of fate, the legal battle actually helped establish Nike's legitimacy. The court ruled that both companies could sell their versions of the Cortez shoe - the design that Bowerman had created while working with Tiger. This meant Nike could continue producing their most popular model while building their own brand. The Tiger Cortez became the Nike Cortez, which remains a bestseller to this day.

The separation from Tiger forced Nike to innovate quickly. Through their new partnership with Nissho Iwai, they established relationships with Japanese manufacturers like Nippon Rubber. In one memorable meeting, Knight handed them a Tiger Cortez in the morning, and by afternoon, they had produced an almost perfect copy. "This is what I'm talking about," Knight reportedly said, immediately placing orders for several models. The break with Tiger, while terrifying at the time, proved to be Nike's liberation. Free from the constraints of being merely a distributor, they could now control their own destiny. By 1974, their first full year of independence, Nike's sales hit $4.8 million, proving that they could not only survive but thrive on their own.

This period perfectly encapsulated Knight's management philosophy: "Break the rules, fight the law" - one of Nike's early corporate principles. They operated right up to (and sometimes over) the line of what was acceptable, but always with a clear vision of building something greater than just a shoe distributor. The messy break with Tiger forced Nike to become what Knight had always dreamed it could be: not just a company that sold shoes but one that created them, shaped them, and ultimately redefined what athletic footwear could be.

From there, Nike began its ascent, but not without some trials and tribulations along the way.

The early 1980s nearly broke Nike. The company completely missed the aerobics boom, watching in horror as Reebok surged past them in market share. While Nike remained fixated on running and performance, Reebok captured the zeitgeist with softer, more fashion-oriented shoes. By the late 1980s, Reebok was outselling Nike.

Salvation came from an unexpected source. In 1984, Nike was struggling so badly that they nearly cut their basketball division. Instead, they made what would become perhaps the greatest sports marketing deal in history - signing Michael Jordan. The deal was revolutionary: instead of a flat fee like other athletes received (Magic Johnson and Larry Bird were getting about $100,000 annually from Converse), Nike offered Jordan a percentage of revenue. Even more remarkably, Jordan would get royalties not just on his shoes but on all Nike basketball shoes above their baseline sales.

First-ever Jordans. Source: The Guardian

The Air Jordan 1 launch was both a triumph and a crisis. First-year sales hit $126 million - dwarfing their modest $3 million projection. However, this figure was somewhat artificial. Nike had stuffed the distribution channel to make the launch appear successful. The following year brought a harsh hangover. Compounding problems, Jordan broke his foot and missed most of his second season. The Air Jordan 2, designed by Peter Moore and Rob Strasser, was a disaster - an expensive Italian-made shoe that Jordan himself disliked. But this disaster led to one of Nike's most important innovations - not in shoes, but in structure. To save the Jordan relationship, Nike agreed to make the Jordan brand a separate division with its own identity. Tinker Hatfield, a former architect turned shoe designer, became Jordan's personal designer. The Jordan 3, with its visible Air unit and Jumpman logo replacing the Swoosh, saved the relationship and launched the modern sneaker culture.

Another one of the most significant developments in this era of Nike was the rise of Rob Strasser, Nike's first marketing chief, who helped transform Nike's approach to sports marketing. Strasser, physically and temperamentally Knight's opposite - a 300-pound force of nature - masterminded the college basketball program with Sonny Vaccaro. They innovatively signed college coaches rather than just teams, paying them consulting fees to have their teams wear Nike. Within a month, they had UNLV, Georgetown, Texas, and Arkansas on board. The strategy created controversy - The Washington Post ran a pearl-clutching article about Nike commercializing college athletics. Ironically, when they mistakenly reported Iowa (instead of Iona) as a Nike school, legendary coach Lute Olson called Nike, asking to get in on the deal. The approach revolutionized sports marketing.

However, this period also saw internal drama. Strasser, after helping build Nike's marketing empire and orchestrating the Jordan deal, had an enormous falling out with Knight. He started a separate division away from Nike's main campus, mandating all new product launches go through his group. This power play led to his departure in 1987. In what Knight would consider an unforgivable betrayal, Strasser went to Adidas, becoming CEO of Adidas America. Tragically, Strasser died of a heart attack just eight months into the job at age 46. Knight did not attend his funeral - a reflection of how deeply the betrayal cut.

The mid-1990s brought the labor controversies to a head. When activist Jeff Ballinger published his report about conditions in Indonesian factories, Nike initially responded defensively. The company's attempts to distance itself, claiming "we don't make shoes," backfired spectacularly. Nike faced boycotts, protests at retail stores, and intense media scrutiny. This crisis forced Nike to fundamentally rethink its approach to manufacturing oversight.

Source: Nike

By the 2000s, Nike had begun a major strategic shift. They acquired Converse in 2003 for $309 million and started emphasizing direct-to-consumer sales. The company also started its digital transformation - in 2006, with input from new board member Tim Cook, they launched Nike+iPod, marking their first major step into digital technology.

More recent years have seen Nike taking bold stances on social issues. The 2018 Colin Kaepernick "Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything" campaign was a watershed moment. Initially controversial - causing a stock dip and product boycotts - it ultimately proved highly successful, adding $6 billion to Nike's brand value.

Under current CEO John Donahoe, Nike is navigating new challenges: the shift to direct-to-consumer sales, digital transformation, and competition from both established rivals and new players like On and Hoka. They're also dealing with inventory challenges and their relationship with Chinese consumers while maintaining their position as the world's dominant athletic brand.

Today, Nike is a $50 billion revenue company, with the Jordan brand alone generating $6.6 billion annually. For the fiscal year 2024 ended on May 31st, 2024, Nike reported revenues of $51.4 billion and a net profit of $5.7 billion, reflecting a 12% year-over-year increase in profit. Even despite facing some headwinds in direct-to-consumer sales and managing inventory challenges, Nike continues to maintain healthy profitability with a gross margin of 44.7%, truly speaking to the competitive moat that the brand itself has come to provide.

Throughout all these changes, Nike has maintained the core principles that Phil Knight instilled: an obsession with innovation, a willingness to take bold risks, and an understanding that their real business isn't just selling shoes - it's selling the dream of athletic achievement. The company continues to operate by one of its earliest maxims that you can still find on its investor relations page: "Nike is a growth company."

RTFKT

Remember when those bored-looking apes took over the profile pictures of almost every celebrity, from actors to athletes, that you know? Those were the best of times and the worst of times. It was the time when NFTs were all the craze when we were all still stuck in our homes going to school or work via our digital screens. It was in a fractionalized time like this when the NFT collectibles studio RTFKT (pronounced “artifact”) was formed by three friends in 2020 at the beginning of the COVID era.

RTFKT gained recognition in 2021 as a groundbreaking digital fashion startup, blurring the lines between the physical and digital worlds by creating next-generation collectibles that combine culture with gaming. The company utilized cutting-edge technology—ranging from in-game engines and NFTs to blockchain authentication and augmented reality—alongside expert manufacturing to craft limited-edition custom sneakers, often accompanied by unique virtual versions. These digital items allowed users, particularly video game enthusiasts, to try on sneakers and unlock special effects. RTFKT didn’t stop there; they also collaborated with prominent crypto creators to design physical shoes that featured imagery from other popular NFT projects, like CryptoPunks and Bored Apes.

In May 2021, the company raised $8 million in seed funding led by Andreessen Horowitz, which valued RTFKT at $33.3 million.

Source: SBC Media

Industry Overview:

Sports equipment and apparel refer to the specialized tools, gear, and clothing designed for various physical activities and sports. Equipment encompasses items such as balls, rackets, bats, and protective gear like helmets and pads, essential for improving performance and ensuring safety. Meanwhile, sports apparel includes clothing like jerseys, shorts, and specialized footwear, often featuring designs that prioritize comfort, flexibility, breathability, and moisture-wicking materials. Together, these products enhance athletes' abilities to perform and protect them during their activities.

At the time of the acquisition in 2021, the global sports equipment market size was valued at USD 331.4 billion in 2021. Today, the market has grown by 13% and was valued at $374.2 billion in 2023 and is projected to reach $991.8 billion by 2034, growing at a CAGR of 9.5% from 2024 to 2034.

This market expansion is primarily fueled by an increase in health consciousness among the general population. More than just an increased interest in sports is a secular change in leading active lifestyles along with a preference for outdoor activities. Activities like yoga, running, and cycling have fueled demand for related apparel (moisture-wicking fabrics, compression wear) and specialized gear (such as durable equipment for CrossFit). Additionally, outdoor activities like hiking and camping have contributed to rising sales of sports gear. Today, consumers are continuing to invest in high-quality apparel and equipment to support active and healthy lifestyles.

Furthermore, growing interest in eco-friendly and sustainable products is creating opportunities. Consumers are gravitating toward apparel made from recycled materials, such as running shoes made from recycled plastics and natural fibers. Brands adopting eco-conscious production methods are gaining favor in the market.

However, the high cost of advanced sports equipment remains a significant hurdle. High-performance gear, such as carbon fiber bicycles and advanced GPS sports watches, comes with premium pricing, limiting accessibility for budget-conscious consumers.

The major players operating in the sports equipment and apparel market apart from Nike include Adidas AG, Asics Corporation, Decathlon S.A., Fila Holdings Corp., New Balance, Puma Se, The Gap, Inc., Under Armor, Inc., and VF Corporation.

Deal Rationale:

The global pandemic significantly accelerated the digitization efforts of many industries, particularly in retail, where brands increasingly adopted metaverse-related technologies through mergers, acquisitions, and strategic partnerships. Nike, the international footwear giant, was no exception. In 2021, Nike’s acquisition of RTFKT aligned with its broader digital strategy, following six previous acquisitions centered on digital growth. RTFKT’s team played a critical role in helping Nike integrate physical products with digital experiences. The acquired company fell under Nike’s newly created "Metaverse Studio," which spearheaded the brand’s virtual expansion.

One reason behind this acquisition was to stay competitive with other major brands like Adidas, which had partnered with Yuga Labs, the creators of the Bored Ape NFT collection. Nike leveraged RTFKT’s expertise to enhance its virtual projects, such as NIKELAND on Roblox and the highly anticipated development of CryptoKicks, which sought to link physical Nike sneakers with NFTs, allowing them to serve as tradable proof of authenticity.

For RTFKT, the acquisition provided access to Nike’s extensive resources and expertise, while the startup maintained its name and core team to preserve its identity in the NFT space. Nike's backing also supported RTFKT’s continued innovation, aiding in its growth and solidifying its place within the digital fashion landscape.

Deal Structure:

Although the financial details of the deal were not disclosed, RTFKT had been valued at $33 million just months earlier, in May 2021. This suggests that Nike invested considerable financial resources into the acquisition, and there are even rumors across the internet that Nike had paid north of 1 billion USD for the acquisition. But obviously, the source of this rumor might just be as trustworthy as your friend’s “Just trust me bro.”

But to at least get an idea of what Nike may have paid for the purchase, we can look at RTFKT’s last financing round as well as their final operating figures before being bought out.

In terms of financing, the company raised $8 million in seed funding in May of 2021, with investors likely holding between 15-20% equity, which values the company at $33 million. In terms of RTFKT’s operating financial performance, the startup had also grown rapidly from $600,000 in revenue in 2020 to $4.5 million in monthly revenue by May 2021. Based on RTFKT’s projected annual revenue of $54 million in 2021 and amid all the hype around the metaverse it wouldn’t be surprising if the offer approached nine figures. This suggested that investors in the pre-seed round could have seen significant returns of over 100% on their investments in just seven months.

Source: Bitcoinist

Deal Discussion:

Financial and Strategic Outcomes

By 2024, however, the landscape around NFTs and the metaverse has shifted dramatically. The initial wave of enthusiasm around NFTs has cooled, with many consumers and investors growing skeptical of the long-term value of these digital assets. The metaverse once heralded as the future of social interaction and retail, has struggled to gain the mainstream adoption many expected.

For Nike, this means that the immediate financial payoff from the RTFKT acquisition has not been as transformative as anticipated. Nike’s NFT sales peaked in 2022 with $185 million in revenue, which only accounted for 0.4% of Nike’s $46.7 billion revenue in 2022, and the number has been decreasing ever since. The company’s digital sneakers and NFT-backed products have found success in niche markets, but they have yet to break into the broader consumer base. Still, the acquisition has allowed Nike to maintain its reputation as an innovative, future-facing brand. In a market where staying ahead of consumer trends is crucial, RTFKT remains a valuable asset for Nike’s long-term strategy, even if the metaverse has not (yet?) revolutionized retail.

Broader Implications for the Retail Sector

While the RTFKT deal was emblematic of Nike’s focus on digital transformation, the broader retail sector is grappling with a fundamental question: What is the future of retail? Even as e-commerce continues to grow, the last few years have shown that brick-and-mortar stores are far from obsolete. Many consumers still value the physical shopping experience, and major brands like Nike have invested heavily in creating immersive in-store experiences to complement their digital offerings.

Under John Donahoe’s leadership, Nike exemplified how retailers could leverage direct-to-consumer (DTC) models to drive profit. Donahoe had an aggressive strategy, which involved cutting ties with major retail partners like Amazon, Zappos, and Foot Locker, which initially appeared successful. The strategy allowed Nike to bypass third-party retailers, improving profit margins by focusing sales on its own stores and digital platforms. Yet, as e-commerce-driven growth started to slow after the pandemic’s peak, the limitations of this model became more apparent. The gaps left by Nike on former retail partners’ store shelves were quickly filled by competitors like Adidas, New Balance, and Puma, as well as upstart brands like Hoka, On, and Salomon. These brands capitalized on Nike’s absence, especially in key categories like running shoes, where Nike’s dominance had been unchallenged for years. Meanwhile, at Nike’s headquarters, the pace of product development slowed. Donahoe took fewer risks on performance-oriented lines, and by mid-2023, Nike's reliable lifestyle offerings, like the Dunks and Air Force 1s, began to lose their appeal. With no new standout products to replace them, Nike’s market share began to erode and what followed was the “Donahoe Dip” in Nike’s stock price.

Source: Bloomberg

What’s Next for Nike and Retail?

Despite the rapid growth of e-commerce, the future of retail is not entirely online. Physical stores still serve a critical role, especially for high-touch brands like Nike that rely on immersive, in-person experiences. For example, Nike’s flagship stores are designed to showcase its products in a way that online platforms simply cannot replicate, offering services like shoe customization and even training studios.

This is where the RTFKT acquisition comes into play: Nike’s future likely lies in a hybrid approach, blending digital and physical retail experiences. While NFTs and virtual fashion may not have mass appeal today, they offer exciting possibilities for brands to engage with consumers in new ways. As artificial intelligence (AI) technologies and large language models (LLMs) evolve, we may see retail experiences that seamlessly bridge the gap between the virtual and physical worlds—allowing consumers to design their own virtual sneakers with the help of generative AI and owning a one-of-a-kind sneaker in the metaverse, before purchasing them in the real world, for example. As crazy as this may sound, the reality isn’t as farfetched as we may think. Just prior to the Paris 2024 Olympic games, Nike showcased a project named Athlete Imagined Revolution (AIR), where the design team created prototype shoes for 13 of Nike's top athletes by inputting prompts of the athletes’ requests and preferences into generative AI models to create hundreds of images that Nike designers then rapidly honed down into single concepts using other digital fabrication techniques including 3D sketching and printing.

Now imagine if this technology was available to the public, and people could create and test their designs in the virtual world through RTFKT. In this context, RTFKT is more than just a bet on the metaverse. It’s part of Nike’s broader strategy to future-proof its brand and adapt to shifting consumer expectations, even as brick-and-mortar stores remain central to its retail strategy.

Source: Nike

As John Donahoe steps down, Nike faces both opportunities and challenges. The company's bold investments in digital transformation, such as the acquisition of RTFKT, have positioned it as a leader in both traditional and virtual retail. However, the cooling of the NFT market and slowing e-commerce growth signal the need for recalibration. Nike’s next CEO, Elliot Hill, will have to navigate a more nuanced retail environment where striking the right balance between online innovation and in-store experiences will be critical.

For the broader retail sector, the future is likely a hybrid of both digital and physical experiences. Brands that succeed in marrying these worlds, while also delivering compelling in-store offerings, will be the ones to thrive. While RTFKT and the metaverse have yet to fully revolutionize consumer engagement, they provide an exciting glimpse into how companies like Nike are positioning themselves for the future.